The other night, I caught the tail end of a special on the The History Channel called “The Sewers of London.” Wow, that must have drawn quite an audience…but I was watching. It described the horrors of cholera and typhus in London before the scientists had sorted out the causes of these scourges. The miasma theory (infection borne by odor) which was wrong, but which nevertheless motivated great public works that led to spectacular gains in public health, dominated the medical establishment.

The Great Stink of the the mid-19th century in London arose from raw sewage dumped right into the Thames, the source of the city’s drinking water. The theory of water-borne disease was not accepted, and Pasteur’s germ theory was not developed yet. Get the stink away and the cholera will leave – it was common sense!

Enter Mr. Bazelgette, heroic engineer of the Victorian Age. (Alas, we have these giants no more!) He built a huge gravity drainage system that directed the city’s sanitary waste to two large pumping stations, from which it was lifted into giant holding reservoirs. (They must have been a frightful sight when full!) When the tide on the Thames was going out to sea, the reservoirs were emptied into the river, and the sewage was carried downstream, away from the city. “The solution to pollution is dilution,” as they say in the engineering world. Today, the beautiful Thames Embankment, imitated the world over, including in New York City’s Battery Park developments, sits on top of the massive gravity sewers designed by Mr. B.

Enter Mr. Bazelgette, heroic engineer of the Victorian Age. (Alas, we have these giants no more!) He built a huge gravity drainage system that directed the city’s sanitary waste to two large pumping stations, from which it was lifted into giant holding reservoirs. (They must have been a frightful sight when full!) When the tide on the Thames was going out to sea, the reservoirs were emptied into the river, and the sewage was carried downstream, away from the city. “The solution to pollution is dilution,” as they say in the engineering world. Today, the beautiful Thames Embankment, imitated the world over, including in New York City’s Battery Park developments, sits on top of the massive gravity sewers designed by Mr. B.

Around the same time, Doctor Snow made his famous map, dear to epidemiologists and cartographers, that showed the incidence of cholera in a neighborhood he studied. He inferred correctly that the cases were all linked to the  source of their drinking water, a local pump. To test his notion, he dared to remove the handle (take note, Mr. Dylan) and the frequency of cholera deaths in the area dropped suddenly. Case closed! Disease is carried by…something…in the water, not by smell!

source of their drinking water, a local pump. To test his notion, he dared to remove the handle (take note, Mr. Dylan) and the frequency of cholera deaths in the area dropped suddenly. Case closed! Disease is carried by…something…in the water, not by smell!

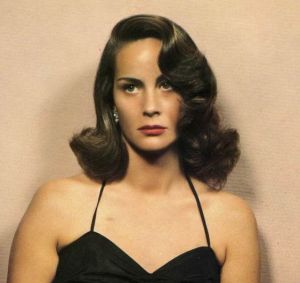

Which brings us to Alida Valli, the woman at the head of this post, the love interest of Harry Lyme (Orson Welles) who meets his ignominious end in the sewers of post-war Vienna in Carol Reed’s film The Third Man. I heard about this film from my mother, at a very young, formative age. Was I, perhaps, conditioned by what Pynchon calls the “Mother Conspiracy, ” just as poor Slothrop was? Is that why I now make my living fiddling with drainage systems and subterranean infrastructure? Well, leaving aside my hydraulic-psychoanalytics(and Freud was, I recall, very fond of hydraulic metaphors) it’s a great film. And if you think I’m the only one who spins strange associations off of this film, read this appreciation of Ms. Valli.

I recently saw Valli in another film, Hitchcock’s The Paradine Case, a not-so-great film in which she plays a wonderful femme fatale. Yep, she did it, she get’s hanged. The film’s location shot of the court struck me as it showed the corner blasted away from a bombing raid – it was shot in 1947.

And on the subject of sewers and culture, check out:

-

He Walked by Night – Richard Basehart kills and is killed in this Los Angels noir featuring a climax in the storm sewers

-

V by Thomas Pynchon – Benny Profane searches for the albino alligator rumored to lurk within the New York system

-

Need I say it, Les Miserables, which includes an entire chapter devoted to the history and importance of the Paris sewers, and includes some deprecatory words on the modern ones

-

Various memoirs of the Warsaw Ghetto – hiding and escaping in sewers was common

-

Adolf Loos’ emphasis on plumbing as the standard by which civilizations are to be judged

-

Gibson’s novel featuring The Stink, The Difference Engine

There are other items I’m sure…send me your finds!

Posted by Lichanos

Posted by Lichanos