When I first read No Orchids for Miss Blandish (1939) by James Hadley Chase, I had no idea what I was in for. After all, this is the crime novel that set George Orwell back on his heels, as he described in his famous essay of 1944, “Raffles and Miss Blandish.“

So much for Raffles. Now for a header into the cesspool. No Orchids for Miss Blandish, by James Hadley Chase, was published in 1939…

Several other points need noticing before one can grasp the full implications of this book. To begin with, its central story bears a very marked resemblance to William Faulkner’s novel, Sanctuary. Secondly, it is not, as one might expect, the product of an illiterate hack, but a brilliant piece of writing, with hardly a wasted word or a jarring note anywhere...

…The book contains eight full-dress murders, an unassessable number of casual killings and woundings, an exhumation (with a careful reminder of the stench), the flogging of Miss Blandish, the torture of another woman with red-hot cigarette-ends, a strip-tease act, a third-degree scene of unheard-of cruelty and much else of the same kind. It assumes great sexual sophistication in its readers (there is a scene, for instance, in which a gangster, presumably of masochistic tendency, has an orgasm in the moment of being knifed), and it takes for granted the most complete corruption and self-seeking as the norm of human behaviour.

I read the Orwell piece years ago, before I encountered Mr. Chase (whose real name is René Lodge Brabazon Raymond), so I read it over again after reading the novel and was puzzled by some of his remarks. A gangster has an orgasm before being knifed? I didn’t read that in the book. Did Orwell read the book, or just go on what he had heard about it? That was before I found out about the complicated publishing history of the novel, detailed in this exhaustive blog post. The violence and sex in the book caused such an uproar that subsequent editions toned down some of it, but Orwell knew only the Ur text. Chase himself, in the early sixties, revised the text to make it seem less dated, so there is a scene in which the gangsters sit watching large television sets, and another in which police helicopters take part in a rescue…while everything else is circa 1935! Getting a hold of that original edition is an expensive proposition, but I’m on the case! I’d also like to know the source of the title, but I’ll get back to that.

The central theme of the story is the rape/abduction of a young woman by disreputable thugs. The rape theme is ancient, of course. The word used to refer to forcible abduction, for purposes of gaining wives, concubines, or slaves, not the violent act of sexual assault, which may have followed the taking, of course. We have the Sabine women being raped, Zeus raping Europa,

innumerable other seduction/rapes of women by Zeus, and perhaps most relevant, the abduction/rape of Persephone by Hades. For it is into a modern mythical/realistic underworld that Temple Drake and Miss Blandish are dumped.

Sanctuary (1931) by William Faulkner, is built around the stuck up, superficial flirt, Temple Drake, who finds herself abandoned to the desires of Popeye, a sickly, impotent, psycho, and his family of half-wits, booze runners, and semi-human beasts. Faulkner later claimed he wrote it for money, and quickly, and the first draft was rejected by his publisher as too indecent. He thought better of it soon after, but then Faulkner went to work again on the text: Today, it is possible to read the original text as well as the published version, shades of James Hadley Chase and Miss Blandish.

The book was praised by some, but for most, it was a moral outrage to be denounced and banned. However discreet and indirect Faulkner was in his prose, Temple is in fact raped by the impotent Popeye with a corn cob, a rather disturbing image when all is said and done.

I think the theme of Popeye’s rape of Temple is echoed in the 1944 stupendous film noir, “Laura,” when Waldo Lydecker, gay or impotent, not sure which, tries a symbolic rape murder of Laura with a shotgun, but she’s too quick for him.

Whatever else he may have had in mind while he was writing it, the book does blow the lid off many aspects of Southern “gentility,” social hypocrisy, the criminal justice system, and maybe the whole idea of civilization itself, a pretty neat trick for any novel.

The novel has been adapted for the movies several times, but the most famous, or notorious I should say, since it is not well known, is the first, “The Story of Temple Drake” (1933), with a sensational Miriam Hopkins playing the flirty, clueless, seductive and stupid Temple who falls into the world of a bunch of backwoods bootleggers dominated by a slick city gangster named Trigger. This film has brilliant, dark, expressionistic cinematography, and the rape scene by Trigger, standing in for the Popeye half-wit,is truncated with a scream, but the lead-in makes clear what is going on. Corn cobs are all around to clue in those literate enough to have read the original text. Hopkins said, “...if you can call a rape artistically done, it was,” but art or not, the film led to the Hays Code having real teeth so that subsequent films dared not go where Temple had gone. Linking all this together, Trigger was played by Jack La Rue, who reappears in the Miss Blandish film as the murderous Slim.

At the conclusion, Temple is called to testify in the murder trial of an innocent man whom she can clear if she reveals her dishonored state. After a struggle, she does so, and faints dead away. Faulkner’s Temple perjured herself, leading the innocent man to be lynched.

Fourteen years separate the Temple Drake/Hopkins film from the Miss Blandish/La Rue film, and in between, there was the super best seller, No Orchids for Miss Blandish, a reworking of the Sanctuary story line. This was Chase’s very first novel, and though he was a Brit, he set it in America. That was part of what got Orwell seething; the importation of American low-class vulgarity into the British cultural landscape, but they loved it! The novel completes the transformation of the abductors from a community of backwoods low lifes to an urban crime gang, this time lead by a murderous woman, perhaps inspired by Ma Barker.

In Chase’s story, some small-time hoods get wind of a roadside club where Miss Blandish (she’s never named, I believe) is going to go out slumming with her beau, while wearing her diamonds worth fifty grand. They catch up with the drunken partyers but the snatch goes bad when the boyfriend plays the chivalrous knight and knocks down a high-strung thug whose response is to beat him to death. Now with a murder rap hanging over them, the hoods run for their hideout, planning to extort a ransom for the girl, kill her, and make their escape. Their plans are derailed when some members of the infinitely more violent and competent Grisson Gang (Grissom in subsequent tellings, and hereafter in this blog) spot them, put two and two together, and trail them to their hideout.

The goings on at the hideout are grim – that’s where the masochistic crook has his pre-knifing orgasm – and the small timers are rubbed out by the Grissom Gang, led by the murderous, psychopathic, and emotionally childlike Slim. They return to their headquarters with the girl and the jewels. Ma, the brains of the outfit, realizes that the authorities have no reason to suspect their involvement; all the evidence leads to the small time thugs, whose bodies have been carefully hidden and the gang murders several inconvenient people who might have information tying them to the kidnapping. Ma executes a ransom collection for several hundred thousand dollars, planning to kill the girl upon receiving it, but Slim has other plans. Despite having never shown an interest in the opposite sex, Miss Blandish’s beauty has led him to an awakening. He wants to be her Beast…forever, whether she wants him or not. Ma is troubled by this new complication – killing the girl is so much simpler – but her murderous son is not to be crossed or the entire gang could be torn apart.

After beating Miss Blandish into submission, Ma instructs her in her new role in life, to please Slim. With the help of drugs administered continually by a former doctor in the gang, Slim has his sex slave. Ma disposes of the hot ransom money at a discount and seizes a local nightclub from its terrified owner, turning it into a “legit” front for their outfit, and raking in the real money. Miss Blandish is kept in a locked chamber where Slim visits her regularly.

All good things must come to an end. A pesky detective working for Mr. Blandish figures out what went down with the jewel snatch and kidnapping, and locates Miss Blandish. The Grissom Gang is expunged in a hail of bullets, but not before taking out a lot of coppers. Miss Blandish is freed, but throws herself out of a window to her death at the first opportunity. Orwell, perhaps speaking as a typical clueless male of his era, says that she had grown so accustomed to Slim’s caresses that she could not live without them, but to me it is obvious that Miss Blandish was psychologically devastated by her months of being raped, and ended her life out of shame and despair.

After WWII, after Orwell had his hissy fit in “Raffles and Miss Blandish,” we get to a film treatment of the novel. The film is British, and most of the actors in it are as well, and they sound it too, despite that the film is set in the United States. Jack La Rue, the only American actor in the film, casts off Trigger to reappear as Slim, transformed into a slick urban gang leader in the prohibition era USA. Instead of playing with switchblades, he works out his inner demons by endlessly throwing a pair of black dice. In fact, “Black Dice” was considered as a possible name for the film, and it is the name the gang gives to the club they take over. But we are in a different moral universe with this film, derived from a successful stage treatment of the book, and one far removed from Faulkner and James Hadley Chase.

Yes, the Grissom Gang trails the small timers to their lair, there is a gunfight, and the gang takes possession of the jewels and the girl, but these two are already connected. The movie opened with Miss Blandish in the lap of society luxury, receiving yet another enormous vase of orchids in celebration of her engagement, but this one has for a card only a note with two black dice and the words, “Don’t do it!” She tells the servant to send them back. “There will be no orchids for Miss Blandish today.” The title of the novel is never explained in the text: I take it to be an ironic existential comment on her fate.

Once Miss Blandish overcomes her shock at being abducted, she calms down and eventually realizes that Slim was the source of the orchids urging her to not get married. And now they are together! How exciting! She feels alive, truly alive for the first time after a stifling existence among the upper crust. Slim is not the deviant half-wit of the source texts, but a smooth operator, attractive, seductive, a bit violent at times, but wonderful to be with. In one scene, Miss Blandish says, “Oh, I know you’ve killed people. You’re cold, you’re hard, you’re ruthless — but …” All in self-defense: they embrace rapturously. Their lips crunch together in a heavy kiss that set a record for duration at that time in cinema. The end comes in the same way – slick or not, they are gangsters – and Miss Blandish kills herself, this time, for precisely the reason Orwell suggested: She cannot bear to return to society life and be without Slim’s caresses. I wonder if Orwell would have enjoyed seeing his misinterpretation of the novel’s text used to conclude what a number of critics have called the worst movie ever made?

At last, we come to “The Grissom Gang” (1971) by Robert Aldrich. (More than fifty years ago! Time for a remake?) We’re back in the USA, Depression Era, but the film is in painfully full color. Everyone sweats, a lot. Ma and her gang mean business, and Slim is back to being a sadistic, emotionally stunted mama’s boy, but he is humanized, a bit. The book’s plot has been snipped here and there to streamline the story, but the brutality of the gang is dark as the night. Mr. Blandish, payer of the ransom, is played by the Aldrich stalwart, Wesley Addy, and is given a truly nasty character more in keeping with the world of Sanctuary than Miss Blandish: He’d rather his daughter be retrieved dead than alive and thoroughly soiled by the ordeal.

Ma and the gang have died in a blaze of gunfire – Ma enjoying every minute of it – and Slim is trapped with Miss Blandish in a barn surrounded by the cops. He declares his love for her; after all, if not for him, Ma would have bumped her off long ago. But he does truly love her in whatever simple and twisted fashion is possible for him, and now it’s time for her to return to her home, so there’s nothing in the world for him but to go out and face the bullets and die. Miss Blandish, who has never become hardened to the killing around her during her ordeal, begs him not to go. “Don’t die for me Slim. I’m not worth it.” She realizes that Slim’s wretched love is the only love she has ever had, and she is grateful for it. But he does go, and he is shot to pieces.

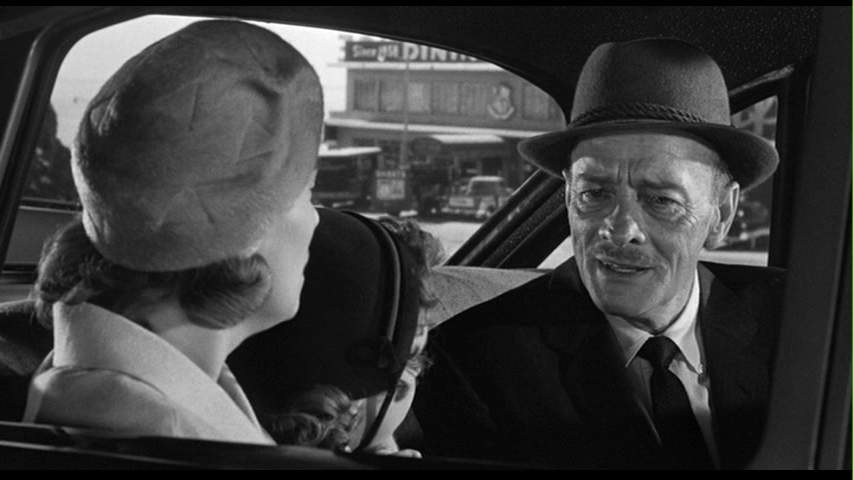

After gazing on Slim’s corpse for a few moments, Miss Blandish is confronted by her father who is clearly disgusted to see her in such a state. She tries to explain: “I was just trying to stay alive. He loved me…” Dad doesn’t understand. He stalks off, telling her that Mr. Fenner, the detective who cracked the case, will see to her. The final scene shows the two of them driving off in a car, she looks back at the barn, bewildered. They’re off to that hotel Fenner has arranged for her, away from the prying press. Will she jump out of the window as she did in the book? Aldrich doesn’t tell, but it certainly seems a good bet.

Posted by Lichanos

Posted by Lichanos

,

,