Theodore Dreiser was a Naturalist in the tradition of Emile Zola, but with a twist. Maybe it was American puritanism, that Calvinist strain, or perhaps some other element of his personality, but man, could he lay on the doom. Having just finished An American Tragedy, all 900+ pages of it, I feel as if I was run over by a steamroller. And I’ve been feeling that way since page 100!

Clyde Griffiths (George Eastman in the Stevens’ film adaptation) has had a stunted youth, the child of impoverished street preachers who include him, even as a very young boy, in their curbside music and proselytizing. Clyde doesn’t feel comfortable with this life from an early age – he always is restless and wanting something different. Eventually, he breaks away, becoming a bellhop, and he enjoys the taste of the highlife that the job, and the tips that come with it, brings. During a wild night out with some friends in he is a passenger in a car that runs over and kills a little girl: he has to skip town, severing his relations with his family yet more deeply.

Eventually, he connects with his very rich uncle, who, feeling guilty about the way his evangelist brother was shafted in the matter of the family inheritance, decides to give the kid a chance in his factory, working from the bottom up. He tells his family that there is no need to admit him to their provincial circle of the social élite, but Clyde besides being handsome and possessed of charming ‘soft’ manners, bears a striking resemblance to his cousin, the heir apparent at the factory. It just wouldn’t do to shun him completely: his face would give the story away and cause talk. He is granted limited access to the Griffiths family.

Eventually, he breaks the rules and forms a romance with a factory girl: she is pretty, and Clyde is subject to powerful sexual urges. He also becomes a regular in the young-smart set of the Griffiths circle, and a powerful flirtation, then a romantic infatuation develops between him and a beautiful girl in that set. He keeps his multiple romantic relations a secret, dooming him when the factory girl becomes pregnant. At his wit’s end, his dream of marriage into society, wealth, ease, material opulence threatened, he plots her murder. She is drowned, mostly through his actions, but there is, to the end, a little shred of ambiguity regarding his intent at the very last fatal moment of he life.

He is immediately caught, despite his ‘careful’ planning, tried, and convicted. He dies in the chair. It is all incredibly slow, detailed, crushing in its inevitability. The characters in this tale are all presented as sympathetically as could be, while the author, from an Olympian perspective, dissects them coolly and dispassionately. It was written and takes place in the 1920s, so some things are not discussed so freely as today, but more so than they were not long before. Clyde’s visit to a brothel while working as a bellhop:

Prepared as Clyde was to dislike all this, so steeped had he been in the moods and maxims antipathetic to anything of its kind, still so innately sensual and romantic was his own disposition and so starved where sex was concerned, that instead of being sickened, he was quite fascinated. The very fleshly sumptuousness of most of these figures, dull and unromantic as might be the brains that directed them, interested him for the time being. After all, here was beauty of a gross, fleshly character, revealed and purchasable

And later:

His was a disposition easily and often intensely inflamed by the chemistry of sex and the formula of beauty. He could not easily withstand the appeal, let alone the call, of sex. And by the actions and approaches of each in turn he was surely tempted at times, especially in these warm and languorous summer days, with no place to go and no single intimate to commune with. From time to time he could not resist drawing near to these very girls who were most bent on tempting him, although in the face of their looks and nudges, not very successfully concealed at times, he maintained an aloofness and an assumed indifference which was quite remarkable for him.

Everyone is ruled by their nature, formed by genetics and the social petri dishes in which they were cultured. The unconscious, and sex, lurks unacknowledged, but powerful. Not just Clyde, but the lawyer who sends him to the chair, the jurors, his defense, the doctors who refuse to give his girlfriend an abortion – they are all locked into the suffocating confines of the social machine. Here’s Mason, the district attorney, determined to see him fry for his crime, and to make a political coup for himself in the process:

Mason was a short, broad-chested, broad-backed and vigorous individual physically, but in his late youth had been so unfortunate as to have an otherwise pleasant and even arresting face marred by a broken nose, which gave to him a most unprepossessing, almost sinister, look. Yet he was far from sinister. Rather, romantic and emotional. His boyhood had been one of poverty and neglect, causing him in his later and somewhat more successful years to look on those with whom life had dealt more kindly as too favorably treated. The son of a poor farmer’s widow, he had seen his mother put to such straits to make ends meet that by the time he reached the age of twelve he had surrendered nearly all of the pleasures of youth in order to assist her. And then, at fourteen, while skating, he had fallen and broken his nose in such a way as to forever disfigure his face. Thereafter, feeling himself handicapped in the youthful sorting contests which gave to other boys the female companions he most craved, he had grown exceedingly sensitive to the fact of his facial handicap. And this had eventually resulted in what the Freudians are accustomed to describe as a psychic sex scar.

In his dreaminess, he has something in common with Clyde, but he was deformed, and now he has that “sex scar.” And there is the town, the jurors, the face of stolid morality, the herd mentality of the Christian rubes, which Clyde’s defense attorney scorns, but treats gingerly by necessity, as he questions Clyde on the stand:

He was a college graduate, and in his youth because of his looks, his means, and his local social position (his father had been a judge as well as a national senator from here), he had seen so much of what might be called near-city life that all those gaucheries as well as sex-inhibitions and sex-longings which still so greatly troubled and motivated and even marked a man like Mason had long since been covered with an easy manner and social understanding which made him fairly capable of grasping any reasonable moral or social complication which life was prepared to offer.

“Oh, I can’t say not entirely afterwards. I cared for her some — a good deal, I guess — but still not as much as I had. I felt more sorry for her than anything else, I suppose.”

“And now, let’s see — that was between December first last say, and last April or May — or wasn’t it?” “About that time, I think — yes, sir.”

“Well, during that time — December first to April or May first you were intimate with her, weren’t you?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Even though you weren’t caring for her so much.”

“Why — yes, sir,” replied Clyde, hesitating slightly, while the rurals jerked and craned at this introduction of the sex crime.

“And yet at nights, and in spite of the fact that she was alone over there in her little room — as faithful to you, as you yourself have testified, as any one could be — you went off to dances, parties, dinners, and automobile rides, while she sat there.”

“Oh, but I wasn’t off all the time.”

Clyde done wrong, but what were his chances in life? Society stinks. Capital punishment is brutal and inhuman. Public officials are self-serving and venal. (Mason is honest, but one of his staff plants evidence to further incriminate Clyde. He needn’t have bothered, but he does anyway.) The social élite are shallow, smug, and uncaring. Society is a machine to grind you down, and it starts on page one and goes on, and on, and on…It’s a pretty damn impressive literary feat, if you can stand it! Dreiser can create a stem winding dramatic courtroom oration as well as he can reproduce the baby talk of a society princess teasing her beau.

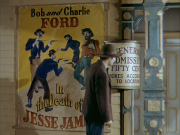

When I began the book, I was struck by how unsympathetically Clyde was portrayed (or at least, without sympathy) compared to the film. As I read on, however, I came to feel that George Stevens had done a remarkable job of adapting the book and bringing forward to the 1950s, both as a narrative, and in its approach to the audience. One of the principal differences that I did find a little bit too much to accept in the film, is that Angela Vickers (Liz Taylor) visits Clyde just before his execution, after being kept completely out of view and out of the testimony of the trial. She still loves him.

In the book, she sends him a brief anonymous, typewritten note that makes clear that she is emotionally distant from him now, although she recognizes how in love they were, and she will not forget him. It is in keeping with the ruthless presentation of class relations that is part of the book – she will get on with her social role in the world – and it is the final, crushing blow to Clyde. As I noted in my post on the film, it is a social melodrama, and such uncompromising realism would have been out of place.

Posted by Lichanos

Posted by Lichanos