There are many fine novels and memoirs about the unspeakable human butchery known as World War I, and Fear (1925) by Gabriel Chevallier, stands very high among them in my view, although it is not as well known as others. One reason might be that it was suppressed by the French government for many years, and, naturally, in the Anglophone world, the English writers are better known. And unlike All Quiet on the Western Front, nobody made a great film out of it.

Each of these books has a distinctive tone: All Quiet is epic in its seriousness and anti-war message; Goodbye to All That by Robert Graves (1929) is mournful and bitter, a wrenching confession of betrayal and loss is how I recall it; Storm of Steel by Ernst Junger (1920) is powerful, and unusual because the author thrived on the horrible challenges of trench warfare, but all are steadfastly unsentimental and unromantic: they are at pains to rip the gauzy cloak of patriotic jabber off the horrific body that was warfare on the front. Paul Fussell’s profound study of the presence of WWI in English literature, The Great War and Modern Memory, contains so much material from primary sources, it reads like a powerful memoir steeped in dramatic irony. The very distinctive contribution of Fear to all of this is its tone of cutting sarcasm and irony that shrinks back from descending into ranting, and its emphasis on the primary emotion of a trench solider – fear.

The author was French, and much of what he describes is characteristic of the French war effort. Englishmen rave against the stupidity of the generals, but they also talk a lot about the flower of the elite classes sharing the trials of the men, and dying with them. The French officer class was notorious for its pig-headed stupidity, and complete unconcern for the welfare of the troops, and it was only the French army that experienced widespread mutinies during the war.

The novel is largely autobiographical – how could it not be? You had to live through the hell to write about it. The young man who narrates it joins up at the beginning of the war, out of curiosity mostly, completely unaware, as was everyone else, of what he’s in for. He is educated, and is granted minor privileges now and then when he’s not on the front line by virtue of his class standing, but for the most part, his lot is that of every other poor soul trapped, waiting to die in the trenches. Here are some excerpts:

He is wounded, hospitalized, recovers, and given some leave to go visit his family. The gulf between the civilian patriots and the men who fight for the cause is unbridgeable:

‘Let me introduce my boy who has just come out of hospital after being wounded.’ [my father] says, shaking hands.

These important men interrupt their games of cards to greet me warmly.

‘Excellent! Bravo, young man!’

‘Congratulations on your bravery!’

‘I say, Dartemont, what a fine chap!’

Then they go quiet, not knowing what further encouragement to offer me. The war is out of fashion, people are getting used to it. Military men on leave are everywhere, giving the impression that nothing bad ever happens to them. And I am just an ordinary soldier, and my fathers’s business is hardly flouring. These gentlemen have been generous to take such an interest in me. …

‘You have some fun out there then, eh?

I stare in shock at this bloodless old fool. But I answer quickly and pleasantly:

‘Oh, gosh yes. I should say so sir…’

He beams happily. I have the feeling he is about to exclaim: ‘Oh-ho, those good old poilus!’ [doughboy, literally, “hairy one.”]

Then I add:

‘…We really enjoy ourselves: every evening we bury our pals!’

His smile goes into reverse and the complement freezes on his lips, He grabs at his glass and sticks his nose in it. In shock he swallows his beer too fast and it heads straight for his lungs. This is followed by a gurgling noise and then a little jet of spume that he spouts into the air and which descends on to his stomach, in a cascade of frothy bubbles.

‘Something go down the wrong way?’ I inquire mercilessly.

The Germans, referred to as The Boche, mount an attack, for which the author’s units are well prepared:

‘We had six machine guns in action right off. Can’t do anything against machine guns!…I never seen so many going down as I did then!’

‘Not as many as I have,’ says the machine gunner sergeant who is listening to us. ‘When we were fighting in open country, I was with the Zouaves. There was one time when there were three of us gunners dug in behind tree trunks on the edge of a forest on a little rise. we opened fire on battalions that were coming out at four hundred meters, and we didn’t stop firing. A surprise attack. It was frightful. The terrified Boche couldn’t get out of the way of our bullets. Bodies piled up in heaps. Our gun crews were shaking with horror and wanted to run. Killing made us afraid!…

There is much more graphic description of the carnage of the front, and it is difficult to read, even when the author polishes off the description with a bit of rapier wit. And then, there is is scathing contempt for the officer class, the directors of the war:

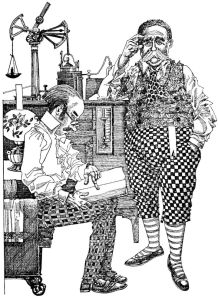

The officers of the colonel’s entourage…are carefully shaved, powdered and scented: these are men who have time devote to their toilet…

Finally the colonel shows up. He’s tall and slim, with a long Gallic mustache, dressed in khaki, cap pulled down over one ear, chest pushed out – very much the musketeer. . . He pulls himself to his full height when he sees a solider, fixes his magnetic gaze upon him, and salutes him with a fulsome gesture which might signify, ‘All honor to you, bravest of the brave!’ or ‘Always follow my plume! [an allusion to a famous statement of Henry IV]. Unfortunately, at the moment of a skirmish, that plume will stay put rather far in the rear…I am only going by appearances, and I do not know the true worth of the colonel, apart from his theatrical salute. But I never trust people who give themselves airs.

His audience over, the captain rejoins us. We leave Versailles…

The historical allusions to Henry, the satirical reference to Versailles – we are in the presence of an educated, intelligent, and deeply comic narrator. His willingness to tentatively suspend judgment, despite having seen scores of men sent to their deaths on pointless missions ordered by men who look like the colonel, is part of his engaging nature.

At one point, knowing the war is grinding down, he delivers, to himself, an impassioned denunciation of everything associated with the entire sick enterprise:

‘I’ve had enough of this! I’m twenty-three years old, I’m already twenty-three. Back in 1914 I embarked on a future that I wanted to be full and rich, and in fact I’ve got nothing at all. I am spending my best years here, wasting my youth on mindless talks, in stupid subservience……My patrimony is my life. I have nothing more precious to defend. My homeland is whatever I manage to earn or to create. Once I am dead, I don’t give a damn how the living divide up the world, about the frontiers they draw in their maps, about their alliances, and their enmities. I demand to live in peace, far away from barracks, battlefields, and military minds and machinery in any shape or form. I do not care where i live, but demand to live in peace to slowly become what I must become. …Killing has no place in my ideals. And if I must die, I intend to die freely, for an idea that I cherish, in a conflict where I will have my share of responsibility…’

‘Daretemont!’

‘Sir?’

‘Go and check where the 11th have positioned their machine guns. On the double.’

‘Very good, sir!’

The photo at the top is from a collection of color photographs, yes color!, taken by the French during WWI, and you can find more here. My guess is that they tidied things up a bit before shooting the pics.

Posted by Lichanos

Posted by Lichanos